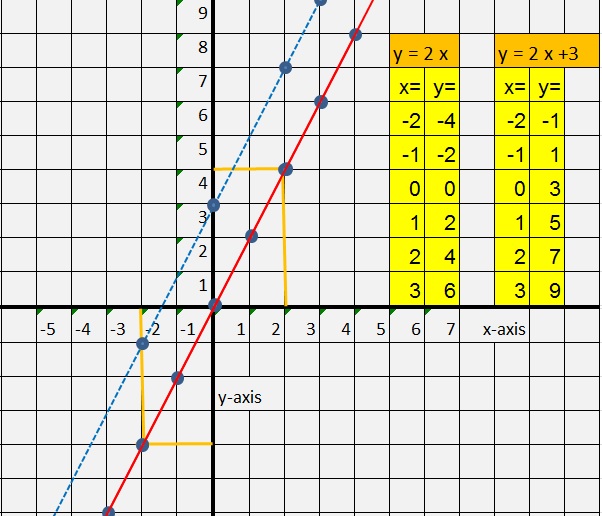

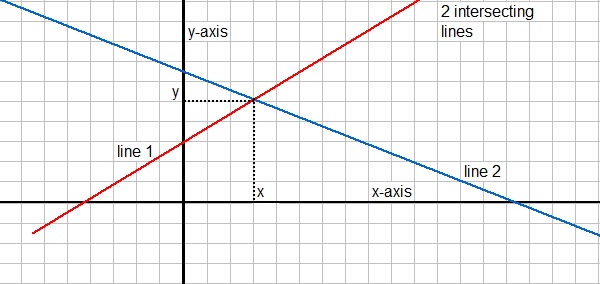

| value of x: | value of y: (which is 2x) |

| x= -2, then | y= -4 (because 2 x -2 = -4) |

| x= -1, then | y= -2 (because 2 x -1 = -2) |

| x= 0, then | y= 0 (because 2 x 0 = 0) |

| x= 1, then | y= 2 (because 2 x 1 = 2) |

| x= 2, then | y= 4 (because 2 x 2 = 4 |

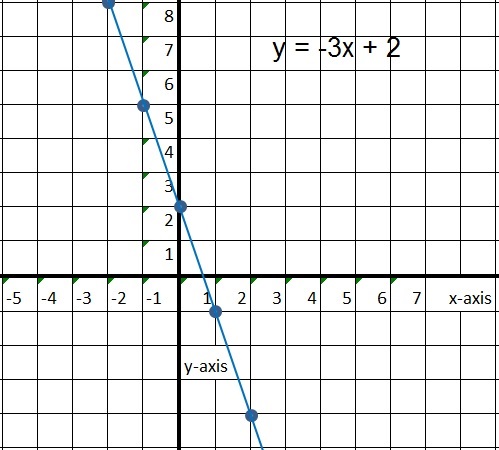

| value of x: | value of y: (which is -3x + 2) |

| x= -2, then | y= 8 (because -3 x -2 + 2 = 6 + 2 = 8) |

| x= -1, then | y= 5 (because -3 x -1 + 2 = 3 + 2 =5) |

| x= 0, then | y= 2 (because -3 x 0 + 2 = 0 + 2 = 2) |

| x= 1, then | y= -1 (because -3 x 1 + 2 = -3 + 2 = -1) |

| x= 2, then | y= -4 (because -3 x 2 + 2 = -6 + 2 = -4 |

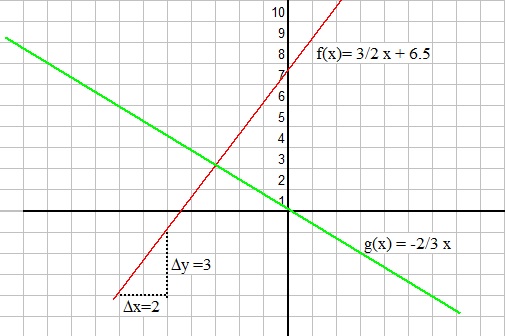

| slope= |

4 - 1 |

= 4 |

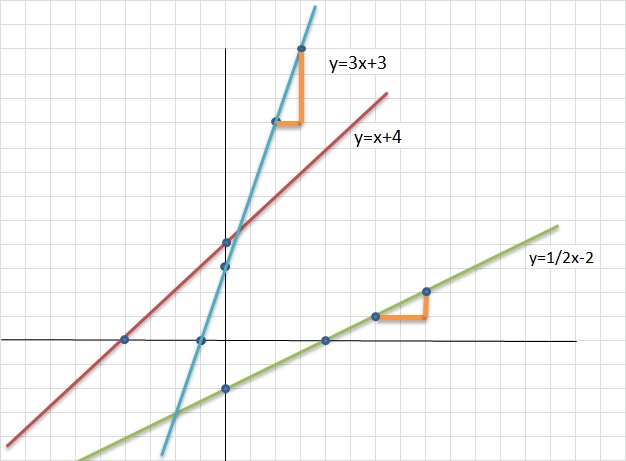

| slope= |

Δy -- Δx |

| y = ax + b | = | slope * x + b | = |

Δy -- x Δx |

+ b |

| slope= |

1 - 4 |

| x: | y: |

| 1 | 4 |

| 2 | 6 |

| 3 | 8 |

| 4 | 10 |

|

Δy -- Δx |

|

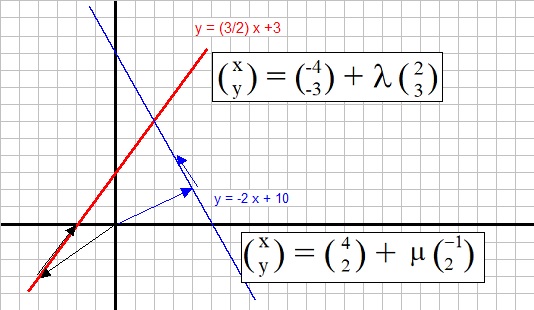

┌ x ┐ └ y ┘ |

= |

┌ -4 ┐ └ -3 ┘ |

+ | λ |

┌ 2 ┐ └ 3 ┘ |

|

┌ 0 ┐ └ 3 ┘ |

= |

┌ -4 ┐ └ -3 ┘ |

+ | 2 |

┌ 2 ┐ └ 3 ┘ |

|

┌ x ┐ └ y ┘ |

= |

┌ 4 ┐ └ 2 ┘ |

+ | μ |

┌ -1┐ └ 2 ┘ |

|

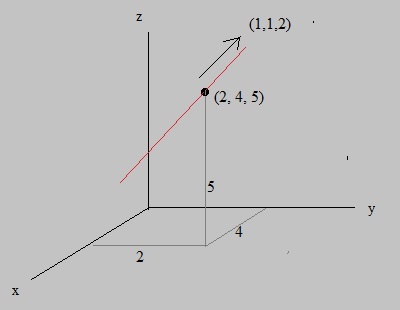

┌ x ┐ │ y │ └ z ┘ |

= |

┌ 2 ┐ │ 4 │ └ 5 ┘ |

+ | λ |

┌ 1 ┐ │ 1 │ └ 2 ┘ |

|

┌ x ┐ └ y ┘ |

= |

┌ -4 ┐ └ -3 ┘ |

+ | λ |

┌ 2 ┐ └ 3 ┘ |

|

┌ x ┐ └ y ┘ |

= |

┌ 4 ┐ └ 2 ┘ |

+ | μ |

┌ -1┐ └ 2 ┘ |

|

┌ x ┐ └ y ┘ |

= |

┌ -4 ┐ └ -3 ┘ |

+ | 3 * |

┌ 2 ┐ └ 3 ┘ |

= |

┌ -4 ┐ └ -3 ┘ |

+ |

┌ 6 ┐ └ 9 ┘ |

= |

┌ 2 ┐ └ 6 ┘ |

| A = |

┌ a ┐ └ b ┘ |

| B = |

┌ c ┐ └ d ┘ |

| A = |

┌ 1 ┐ └ 2 ┘ |

| B = |

┌ 3 ┐ └ -2┘ |

| A = |

┌ 1 ┐ └ 2 ┘ |

| AP = |

┌ -2┐ └ 1 ┘ |

| A = |

┌ a ┐ └ b ┘ |

| B = |

┌ -b┐ └ a ┘ |